“Cut your hair so you can look like a nice boy! Not a ruffian!” I can’t recant the number of times I’ve heard West African aunties and uncles tell that to my fellow peers with eccentric hairstyles. They look pon (patois for “upon”) the dreads with dread. That’s partly the reason why the hair was named dreadlocks by Europeans. It symbolized the fight that Rastafarians in Jamaica (and the Caribbean) were willing to put up with their oppressive systems at home and abroad. The notorious term Babylon came to represent such. In my household, dreadlocks were the representative of Babylon.

I am a first generation Ghanaian-American, specifically from the Akan people. It’s not unheard of to hear today’s Ghanaians, especially those from my grandparent’s era to say the hairstyle is a representation of “witchcraft” or “the hair is unprofessional”. I mean, they are not lying. It is true. To an extent. Children who were chosen by the abosom (the spiritual gods of nature), were taken early to be students of the “occult” and learn the ways of healing and communication with nananom (ancestors). They would become the abosomfoɔ, the spokespersons of the gods.

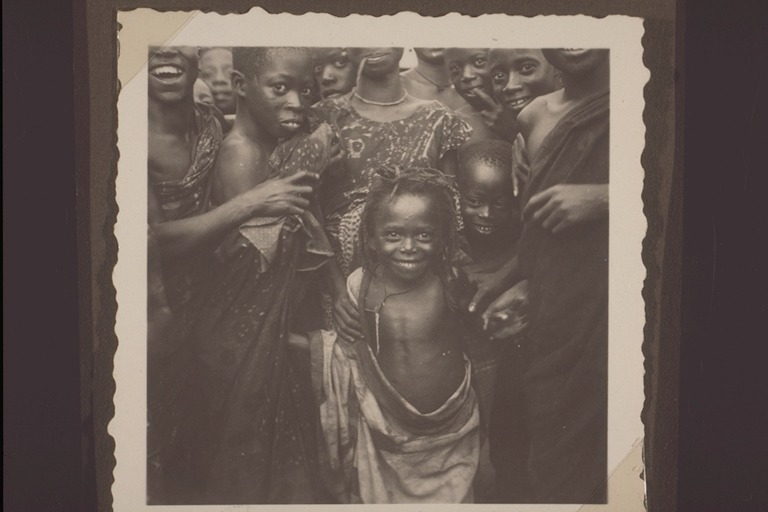

The expression of one’s hair throughout West Africa (and worldwide) has been one of art and symbol of power. As an Akan, it shocked me to learn that many men in the pre-colonial era (and especially soldiers) made their hair in long elaborate braids resembling beautiful weaves, accompanied with cowrie shells (currency during those days). The Adinkra symbol “Kwatakye Atiko” resembles one of these beautiful works of art.

Courtesy: Basel Mission Archives

It wasn’t only Akan. Priests of the Yoruba ethnic group wore locks and were called babalowo. The Woodaabe Fulani stock have a men’s fashion competition and they sport make-up, paint and elaborate hairstyles including thick braids and locks. Igbo men of Nigeria wore locks as well (before it’s demonization by Christian missionary schools). The Dogon peoples of Mali have ceremonies central to their religion in which people wear locks and go in a trance, putting their audience in a state of awe. These examples give us a well-trodden pattern of hair being used as a symbolization of power and individual expression.

That is one of the lasting effects of British missionary influence and colonization that lasted for nearly 100 years. Of course, like most institutions that are embedded in society, little has changed and disdain for “non-Christian” values is now present in large swathes of West Africa. Likewise, in the Bible, when the early Christians were excited to uphold a picture-perfect standard, such standards became the norm in West African Christianity. We are the new Christians, with most families having no more than three generations worth.

Are dreadlocks bad because they represent the custodians of evil inflicted against their ancestors. Are they good because it represented healing and spirituality that empowered the community? Or is cutting my hair good so I can appease the Christian doctrine that went hand in hand with the British “Babylon System ”? Which “Babylon” do I seek to demolish?

“This is witchcraft!” “This is of the evil that goes against God’s word.” “Blasphemy and Negro juju!” said the English colonial masters who were able to predate on the wounds suffered at the hands of the Akan religion. Expression of oneself through hair has been one of the most focal targets in this war against “blasphemy”. Why wouldn’t it? The daunting power of silent chandeliers threatens the status quo. An antidote to the madness would be nice but unfortunately, it is the bread and butter of humanity. We have culture wars every day. Religious wars every day. Wars between psyches every day. May the authenticity in each individual win.