This is my first blog post from the continent of Africa, specifically the 10-island archipelago nation of Cabo Verde. It is located just off the coast of Senegal & is not well-known amongst most people, especially in the English-speaking world. Probably because the country is small, mainly Lusophone and speaks Portuguese & Kriolu (mixed African/Portuguese language). That can come as a bit of a shock for those of us used to African countries having more of a French/English influence. They also have such a WIDE range of looks, shades, and hair here, very much somewhat akin to people in countries like Brazil, Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico. Why is that? Why, on average, do they not have more similar features to people living in adjacent mainland Africa? Well, to answer that question, this is the first country, colony or place where the (forced) union of European overtones and African undertones in a neutral, new land came to be. It was not any area in the Americas/Caribbean. It was located just off the coast of mainland Africa.

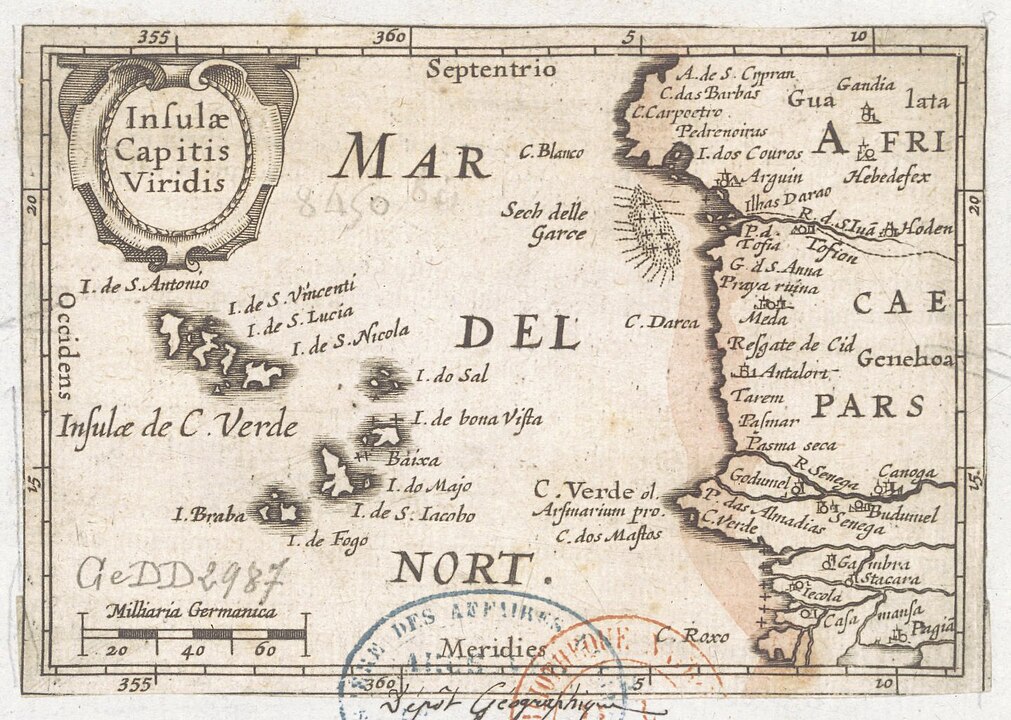

The story of Cabo Verde begins around the mid-15th century. Of course, as I stated in blog articles prior, the Portuguese had started to establish relationships at that time with Atlantic African states and peoples spanning today’s Senegambia all the way to Sierra Leone. In initially small numbers, sailors, traders and adventurers ( lançados as they were called) started to move there to engage in economic relations, principally in slave trading. Due to the area being in the domain of Atlantic African peoples, business was usually done while being under the yolk of leaders in their respective residential areas. Here, they paid taxes to authorities, and established business relationships between other European nations coming to trade and even acted as liaisons between various Atlantic African polities at times. Nonetheless, this inability to have complete autonomy & a desire to have an exclusive base had the Portuguese crown/lançados itching for a base of their own. On their own terms. In 1462, they found their gem, thanks to explorer Diogo Gomes. Being the first to explore the uninhabited islands of Cabo Verde, he boasted of the beauty of the birds, vegetation and rivers on the biggest island of them all, Santiago. This prompted further exploration of the surrounding islands of which they found uninhabited and doable & by 1509, the entire archipelago was colonized.

Colonization, of course, meant that Cabo Verde needed to be settled, and the settling of the entire area required many resources from inside and outside the archipelago. Lime, marble, lime, floor and roofing was mainly imported from Europe. Wood from island trees had to chopped at a fast rate (which unfortunately, destroyed much of the vegetation & the delicate ecosystem). Most importantly, there was also a need for an immense amount of labor, the vast majority of which came from the adjacent Upper Guinea area. The forced migration that coincided with the need for labor marked the first time color began to become the primary markers for status and your position in society & the first time that enslaved labor was primarily for producing products for sale. After making Ribeiro Grande (Cidade Velha) their (now former) capital, production enterprises settled on horse breeding, growing cotton and producing cloths such as Panu di terra. Waves of weavers from Fula, Sereer, Wolof and Mandinka lands were imported to the island to do this work, in their bid to copy the business model used by the North Africans/Arabs.

Now that I have discussed the initial colonization of Cabo Verde, we must now revert back to the lançados, a term which now included exiled Jews and “New Christians”. Their origins were mostly from Portugal, Genoa (Italy) and Aragon (Spain) & they moved to Cabo Verde and the adjacent Upper Guinea en masse during the colonization of this area. Interestingly enough, many were exiled folks fleeing prosecution or who were regarded as criminals (degregados in Portuguese). They grew in number, “casting themselves out of Iberia” and intertwining themselves with people like the Wolof, Serer, Beafada, Baga, Papel as well as the Cassanga to an extent. They were rejected by more de-centralized peoples such as the Balanta, Djola and the Bijago (at times) due to mistrust of Europeans. Here, they grew in number taking Atlantic African wives (with whom they had many children), adopting spiritual and cultural customs like scarification and tattoos. Their mixed descendants would go on to inhabit the coastline ranging from the Senegal River to the Port Loko region in today’s Sierra Leone, carrying on business endeavors established by their fathers.

Mixed union relationships (on the mainland of Africa), combined with the settling and business movements of Cabo Verde, led to the prosperity of the archipelago colony, who scoffed at their overlords in Europe. Obviously, the Portuguese crown hated this because taxes were not being paid to them and made a decree in 1474 with so that “illegal trade” by (at least) Cabo Verde lançados could be regulated. As Cabo Verde prospered, even more labor was needed. This led to the astronomical uptick of forced migrations amongst the very peoples in Upper Guinea the lançados lived amongst. Coming from diverse backgrounds to a neutral area, the world’s first creole culture slowly but surely started to develop.

Here, although there was a strong disdain for darker hues, there was less segregation compared to Northern European colonies & this society was slow to incorporate the English, Dutch, French & English version of very harsh plantation slavery when the sugar boom of the 1640’s took hold. There are multiple reasons for this. Well, one, products like sugarcane never really took off here. There was also the collapse of many enterprises after the 1640s, leading forced migration to slow to a trickle. Combine those factors with high rates of manumission (called alforria) & you get a society with a large, free colored/Atlantic African population. Sexual relations between Europeans and the African (although very much violent and forced) had higher rates of consent than the colonial societies established in the New World afterwards. We can see why many in the forced migrant proletarian class felt an incentive to abandon the cultures they lived in back home and adopt to this new, mixed culture. So much so, that it wasn’t rare for those enslaved to even accompany merchant ships back to the Upper Guinea to assist in slaving enterprises.

Due to the proximity between mainland Africa and the Cabo Verde Islands, not all was lost in the ways of their Atlantic African ancestral vibes. Kriolu was developed around this timeframe so that communication between these peoples of various backgrounds could be way smoother. Holding the title as the first Creole-based language (in terms of African/European origins), much of it was influenced by the forced migrants of the Wolof, Sereer and Fula during the 1500s/1600s and later also the Mandinka during the 1700s. The bulk of the vocabulary is Portuguese, but word formation & semantic structure is derived from the African peoples I listed earlier. Here are some words that derive from those in the Upper Guinea:

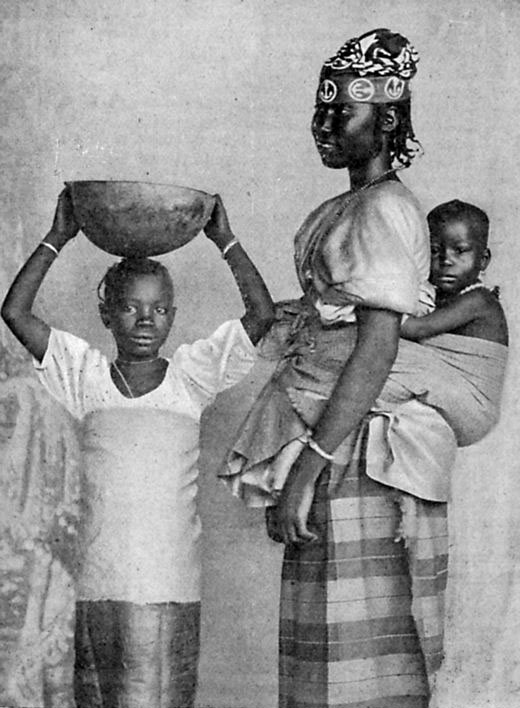

- Bombu: the act of mothers carrying their baby on one’s back (Derives from the term Bamu among the Bambara subsection of the Mande)

- Djurdjur: hurried (Derives from Fulbe Jurjurta)

- Mafafa: Yams (Derives from Biafada Afafa)

- Tabanka: a type of carnival tradition (derives from Temne Kabanka originally meaning fortification)

- Kankaran: a type of mat woven from leaves (derives from the word Kankourang among the Mandinka subsection of the Mande)

According to Nicholas Quint, a linguist, these are a few of the 78 words (and counting) of Atlantic African origin in Kriolu. Aside from these words, music genres such as batuque, tools such as the pilon, a bowl in which one pounds (kotchi in Kriolu) food in, instruments like the cimboa and other markers of Cabo Verde emphasized a spiritual creolization of not just Europe and Africa but also between Atlantic Africans themselves coming from the mainland. Especially between the years of 1460-1660. These people had to create new realities amidst a new era, even making nice with other Atlantic African people they may have deemed as the enemy not too long ago.

As time progressed, the society and its majority Atlantic-African derived work force continued to be “Latinized” in a sense, many receiving baptisms and participating in building and upholding Christian Catholic values. The society & business model built in this area would also become the blueprint for other islands near Africa/Asia like Sao Tome & Principe as well the Canary Islands (owned mostly by the Spanish). Not to mention the colonists from Iberia and other parts of Western Europe who would make it to the Americas. So, in a nutshell, Cabo Verde served as a pioneer for what was to come. An easy way for European values to be freeform outside of its borders. For goods destined for global markets to be produced/ manufactured using a cheap, proletarian labor base. Colonial societies, built on European-based values & upheld (at least that was the expectation) by the majority Atlantic African population. Mixed-race populations. Maroon societies. Globalized economies. Most importantly, it served as an arena for mental conflicts pertaining on how to adapt and live a life so far from what many experienced on the mainland. Primarily for those of Atlantic African descent. Going to Cidade Velha, I felt that. I felt an African spiritual mother energy through the pilon. Panu di terra. The music. The way markets were dominated by women merchants and the way they carried things on their head. Yet, I also felt the energy of their Portuguese fathers. Through the structure. The laws of the land. What a marriage. The face of the nation versus the spiritual African undergrowth.

Initially, my plan was to spend 6 months here, but I think it needs to be a come and go thing. I want to be able to catch on to the energies here. 6 weeks here and I can emphasize with these forced migrants. The cultural and language barrier is crazy. And I have the luxury of locking myself in my apartment & using my phone. But with time, one may be able to understand the story of this place, a country which gave the blueprint to the “New World” which became the world we live in today.